Somethings been rattling around in my head for a long time.

|

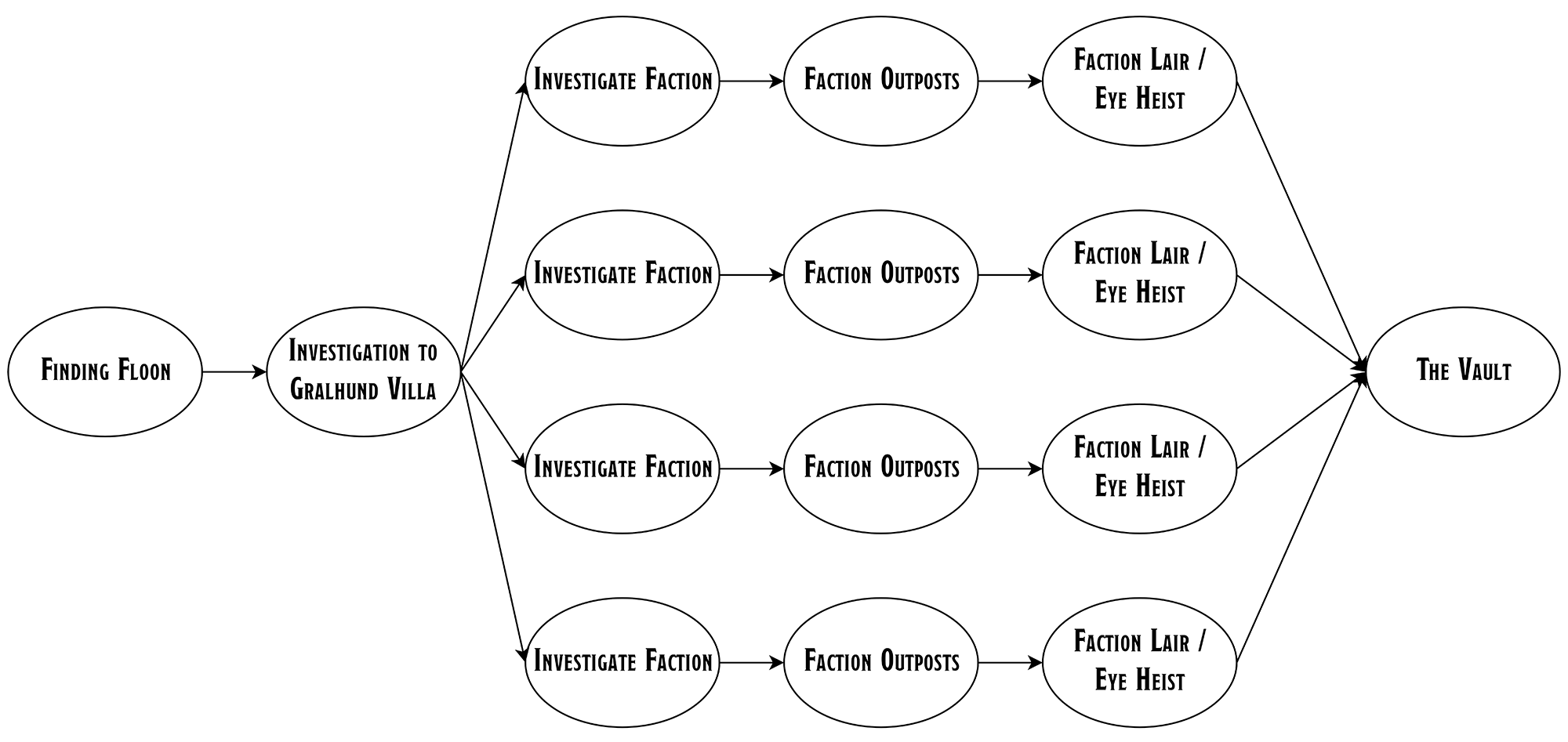

| The core structure of the Alexandrian Dragon Heist Remix |

I've been running RPGs for about a decade now. I started with 5e when it was pretty new, had a good time, and slowly became disenfranchised with its myriad problems. Along the way I found a lot of great advice, especially from Matt Colville and The Alexandrian, but for a long time I mostly ran either published modules or homebrew adventures that were in a similar style.

When I switched to Pathfinder 2e in 2020, I didn't really have problems with the rules themselves. There are still things that don't quite match my preferences, and certain things that I'd probably have done differently, but for the most part the system just works. If I'm too tired to make a call, the game has me covered. I don't have to worry about PCs accidentally becoming overpowered or trivializing an encounters due to a broken rules interaction. And if I do have the energy to make a call that's outside-the-box, or the players come up with an idea clever enough that I want to let them trivialize an encounter, I always have the freedom to do so.

With less work to do hammering the rules into place, however, I could focus more on the adventures themselves. My first real project on this blog was Remixing Strength of Thousands Book 2 in the style of the Dragon Heist Remix, where I deconstructed the grab bag of random quests and put them back together into a more cohesive whole. To date, it's my second most popular series after my Red Hand of Doom Conversion. Ever since, most of my blog has been doing the same - tinkering with adventures to make them more fun to run and play - but the series that finally crystalized my main point today was the one about Negotiations in Mzali.

Now, you might say, "Why do you need to tinker with Pathfinder 2e Adventure Paths? They are so much better than 5e adventures!" And that's true! Genuinely! I love APs, but they still often have problems of their own. Probably the most common complaint about them is about how over-complicated a lot of subsystems are, and I think that is often true! If you've been following this blog for a while, however, you might guess that to me those are just symptoms of a larger issue: structure.

This series is about Scenario Structures: what they are, why they're important, and why Pathfinder 2e would benefit from more of a focus on them. That's right, I said series - as you might be able to tell from the length of that intro, this is a topic I've thought a lot about, and it's gotten a bit away from me. Here's my plan for this series (I'll update it as things develop):

- Introduction & Defining Terms (this post)

- Pathfinder 2e Subsystem Analysis (focusing on Encounter Structures)

- Pathfinder 2e's Infiltration Subsystem

- Pathfinder 2e's other Scenario Structures

- Towards Better Scenario Structures

- Dungeon Crawling

- (I plan to add several other articles on different Scenario Structures, but that's likely a ways off unless I feel unexpectedly inspired)

Let's jump into Part 1!

Defining Our Terms: What's A Scenario Structure?

I'll be basing a lot of this post on this article and the surrounding series, so I highly recommend you give that as much of a read as you can!

As Justin talks about in that series, a Game Structure answers the questions: "(1) What do the characters do? (2) How do the players do it?" However, as he discusses in part 2, this can either be a Micro Structure like an individual ruling or a Combat on the one hand, or a Macro Structure like a Dungeoncrawl on the other hand. "At the macro-level, game structures become scenario structures. These larger scaffoldings determine how the players move through complex environments (physical, social, conceptual, or otherwise)."

So, put simply, an Encounter Structure is something that helps the GM run a discrete chunk of play, whether a combat, a chase, or an interrogation. A Scenario Structure, on the other hand, helps the GM connect the dots between encounters over a longer period. Examples include Mysteries, Dungeon/Location Crawls (and many other types of Crawl, such as overland travel Hex Crawls or Point Crawls), Heists, or even a Party! See this article for examples in action.

The Importance of Structure

One of the big selling points for Pathfinder 2e is that it structures things much better than other, similar games. On the character side, characters are interesting and impactful starting at level 1, there are meaningful choices at every level, and there is a wealth of options while still keeping things balanced and constrained. On the rules side, the Combat Rules are dynamic, engaging, and filled with meaningful choice, and while other Encounter Structures like Chases are less complex, they still have solid structures to them to help GMs run them.

What Pathfinder 2e does not spend much time on is the connection between those Encounters. The most common Scenario Structure in PF2 and similar games is the Dungeon, but when there isn't a specific Dungeon Crawling procedure, this tends to devolve into "deal with each encounter in the room it's set in." Most other PF2 Scenario Structures are even less fleshed out, either a linear sequence of encounters that happen whenever the GM decides or a mish mash of things that the PCs can deal with in any order. Is that, bad? I mean, you can certainly run a game like that! If the encounters are cool enough, your players might not even notice! However, there are several reasons why having a more fully developed Scenario Structure is important:

- Tracking Details. Tracking time explicitly makes it much easier to remember things like torch or spell durations. Writing down that you should deduct rations after each day of travel makes it much more likely that you'll remember. Having a little checklist to refer to means that you're less likely to miss things, and if you do you're more likely to notice them later and fix them.

- Depth of Play. If the rules for Exploration boil down to travel pace, a single choice of Activity, and the occasional Perception check, then there's no reward for engaging deeply with, say, a dungeon as a whole unless the GM specifically adds it in. I've noticed a lot of groups treat Exploration and Travel as basically just breaks in between the "interesting bits" - encounters - rather than interesting in and of itself. As OSR games make clear, however, exploration can absolutely be an interesting and engaging part of play, and by stealing things from the OSR I've been able to do that in PF2 as well. This applies to other scenario structures as well, though Dungeons are the most obvious.

- Framing. Jumping off of #2, regardless of how much more complex the rules themselves for Exploration are, just having more of a structure or ruleset can help shift the players focus towards it (especially in as rules-focused a game as PF2).

- If you explicitly ask them for navigational details, that prompts them to think about the best path. If you make the PCs track rations, they have to think about how many rations to carry and how much inventory it's worth devoting to that. If you openly keep track of time, then even if there are no consequences for wasting time, it still gets the party thinking about it - and if there are sometimes consequences, they will tend to act like there always will be. The more the players are thinking about all that, the more they'll start to think about things that aren't even covered by the rules.

- On the other hand, if you skip past all that framing and get right to "the good bits," the players will do the same, and are less likely to think further than the next bad guy to kill or the next hazard to disable.

- Some examples of cool things that better Exploration framing has enabled in my games includes using terrain/traps/etc. from other areas to gain an advantage in a fight, pitting factions against each other so that you don't have to fight them both, choosing whether to push on while injured or risk taking the time to heal, ambushing patrols or drawing enemies out of a given area, and much much more.

- When PCs engage on the Scenario Level, it can even lead to huge, unexpected changes where the PCs take initiative and start making things happen in really unexpected ways!

- New GMs. While experienced GMs might be able to wing it well enough, newer GMs won't! Giving them a more solid foundation to work off of is essential to not only helping them run this scenario well, but helping them learn to run them in the future as well.

- You Already Have One. Every scenario has a structure, whether an informal one that happened by accident or a formal one that was put there on purpose. Why not design your Scenario Structure to make it as compelling as possible?

All that to say, while you can run a perfectly fine game without defined Scenario Structures, by doing so you miss out on a lot of potential depth and nuance that can lead to some really interesting moments! This applies to non-Exploration Scenario Structures as well, such as Overland Travel, but I think it's the clearest with Dungeon Exploration.

A Brief Aside on the OSR

I have a strange fascination with games in the Old School Renaissance (OSR), though many more accurately fall into the so-called New School Renaissance (NSR) or the Post-Old School Renaissance (POSR, pronounced "poser"). I've gotten a ton of value from reading various OSR blogs and systems, I love modern OSR adventure design (basically just big sandboxes with quest hooks pointing everywhere and a ton of fun stuff to interact with), and I'm even making my own RPG that was originally described as a mix of PF2 combat and OSR sensibilities (though I've moved a bit away from the OSR influence by this point).

All that being said, I call my fascination "strange" because I've only run a handful of sessions of OSR games! I think it holds a lot of attraction for me because it's so different from modern styles, but ultimately the OSR has a lot of problems too. Me and my players tend towards caring about stories and characters first, in a way that kind of works with PF2's focus on combat and heroism, but definitely struggles against the gold-for-XP approach of a lot of OSR games. Besides, isn't the OSR dead anyways?

Relevant for our purposes, it does one Scenario Structure much better than modern games like 5e and PF2 - Dungeon Crawling! - but it tends to offer very little help for anything else. Some argue that its more freeform base rules makes it much easier to improvise with, and there's certainly some degree of truth to that, but I still think there's a ton of value that having more specific scenario structures can add.

Looking Ahead

The ultimate goal of this series is to outline comprehensive Scenario Structures. Ideally, these should be relatively painless for GMs to introduce into their games, even if running published APs, and they should list places where the GM will likely need to do some work (e.g. setting deadlines, creating random encounter tables).

Before we do that, we'll want to take a stroll through the various Subsystems that already exist. We'll first look at the Encounter- and Campaign-level subsystems to orient ourselves to how PF2 subsystems function. Next, we'll look at the Influence subsystem, which is in my opinion the best Scenario Structure that PF2 has currently, in order to see what makes it work and what holes it has. We'll then look at the other Scenario Structures that PF2 has and see where they need buffing up. Finally, we'll go through a bunch of Encounter Structures to see how we can improve on what's already there! I already did Dungeon Crawls, and will probably do more once I finish the rest of the series.

No comments:

Post a Comment